MIRAR HACIA ARRIBA, LUEGO MIRAR HACIA ABAJO Y VOLVER A MIRAR HACIA ARRIBA OTRA VEZ

Exposición individual en Galería Nordés (A coruña: Febrero, 2024)

(texto al final/ Text at the end)

Fotografías/ Pictures: Roi Alonso

ESP/ENG

Se secan en el sol, si hay.

Placing damp bowls on the drying.

Se echa el baño. Putting on the enamel, on the inside only.

Se cuecen. Marchan en las cestas.

R. Matilda.

A veces es interesante mirarse desde la perspectiva del que te ha mirado antes. Otras veces lo es el mirar algo que nunca has visto pero que resulta de algún modo familiar. Existe una mirada que exotiza lo externo y también una que convierte en signo lo propio mediante su auto-representación repetida. Las dinámicas de poder se entrelazan entre el observador y el observado, también entre territorios y, de igual modo, pueden ejercerse de forma espacial a partir de los sistemas de colocación.

Esta muestra se asienta en dos viajes que son, en realidad, el mismo. El mío, de Galicia a Nueva York y de regreso a Galicia y el de Ruth Matilda Anderson, igual pero en sentido contrario. La relación entre ellos me permite trabajar con imágenes y significaciones de ambos territorios que se emplean y se analizan a través de diferentes capas de observación e interpretación.

En las imágenes capturadas por esta americana en Galicia en la década de los años veinte del siglo pasado, observamos prendas y camisas, tanto vestidas como colgadas para secarse. También contemplamos joyas y ornamentos, elementos utilizados para la fotografía, y trajes que no se visten, sino que son extraídos de armarios y arcones para su inmortalización. Este trabajo, necesario a nivel patrimonial, puede resultar engañoso si consideramos la imagen fotográfica como prueba de veracidad. De manera similar, observo la nueva ciudad desde mi perspectiva escudriñadora pero también turística del que mira y se sorprende en lo ya conocido. Lo familiar al haber visto este lugar en numerosas películas y también al visitar este archivo fotográfico de nuestro pasado.

Por otro lado, el extrañamiento de Galicia que emana de estas imágenes se produce también desde la mirada del que vive en ella, al observar un pasado diferente y unas ciudades transformadas. Mi extrañamiento se desplaza igualmente hacia lo nuevo: el tamaño de los edificios, los autobuses escolares o las animadoras americanas, que acaban interesándome tanto a nivel de estructura como por ser una actividad popularmente femenina y, además, algo denostada. Estas expertas en construcciones espaciales y sororidades tridimensionales me recuerdan a las apañadeiras de Niñodaguia, soportando enormes cestas de cacharros sobre sus cabezas. Los ejercicios y formaciones de animadoras y los sistemas de apilado y carga siguen unas normas físicas básicas de disposición y carga que pueden trasladarse al lenguaje escultórico. La verticalidad se presenta como una constante en esta significación de poderes, desde los rascacielos hasta el ímpetu humano por elevarse para obtener una posición privilegiada, para observar desde arriba y estar más cerca del cielo.

En Mirar hacia arriba, luego mirar hacia abajo y volver a mirar hacia arriba otra vez trabajo con lo que está encima de nosotros y lo que está debajo, lo poderoso y lo humilde. Pies y calcetines, cuerpos y ornamentos, tejados, cargas, antenas y pompones. Sus faldas plisadas y nuestras camisas se confunden con tejados y bolsillos. Los picos de aquí y de allí se mezclan con pies descalzos y también con calcetines, representación de aquello que está más cerca del suelo. Lo de arriba y lo de abajo significan y en las obras presentadas se transmutan. Lo puntiagudo ahora es vaso, recipiente o cuenco y lo que está más abajo, cerca de la tierra que sirve como cimiento del cuerpo se eleva. Las tejas funcionan como cuencos, las faldas no cubren nada. La bisutería funciona como ornamentación de bajo presupuesto, como pose y como representación. Esto alude de alguna forma al posado fotográfico, ponerse de domingo, los zapatos del domingo. Hay capas y capas y filtros y filtros transparentes proyectados sobre las imágenes por parte de la fotógrafa y también por parte de las receptoras de dicha fotografía. Esta superposición de transparencias me interesa como veladura y filtro.

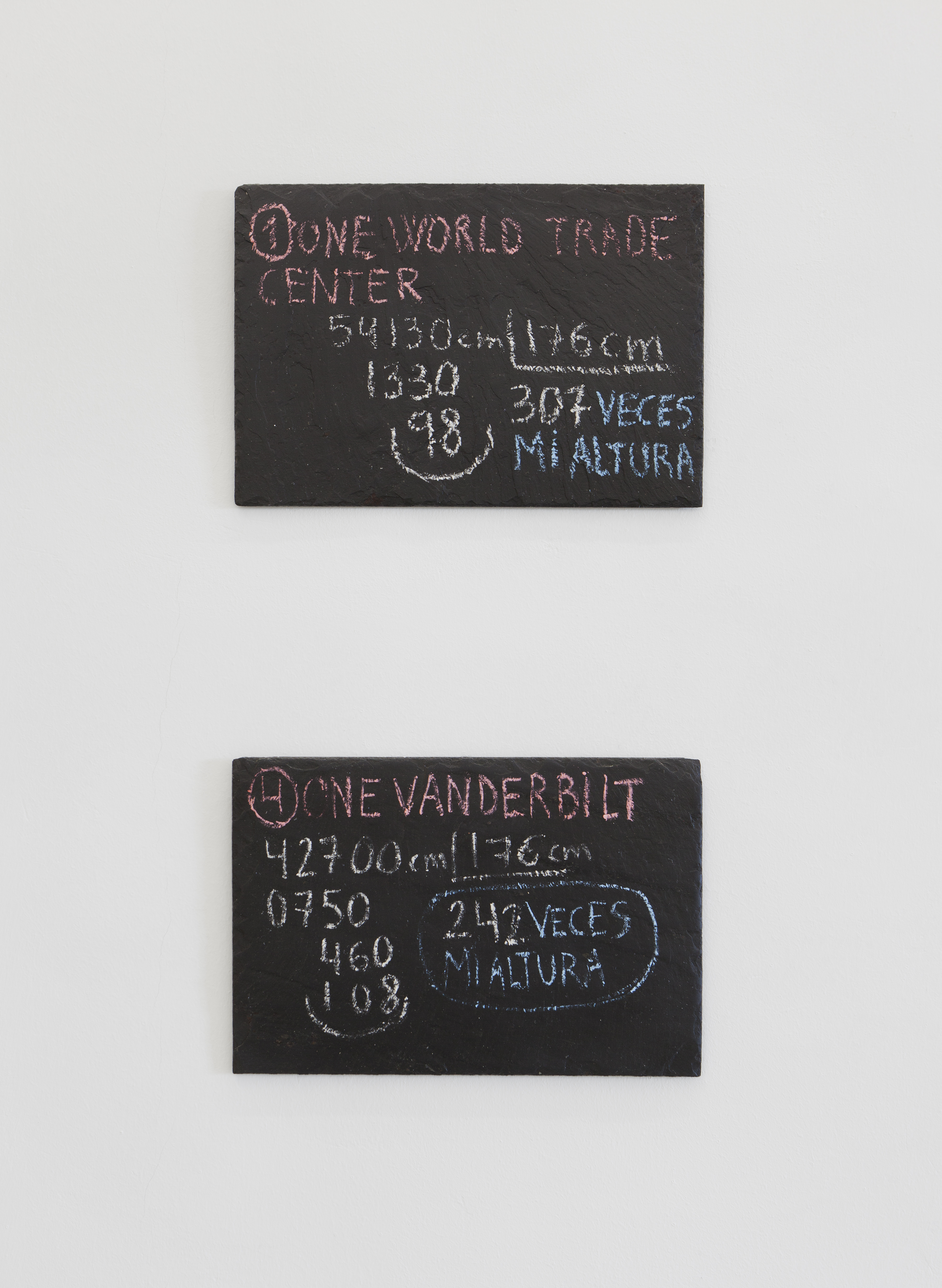

Las formas propias de Niñodaguia se revisan y se transforman, en Oito femias deitadas y Oito machos recipientes, parto de formas de la alfarería tradicional de este contexto, volúmenes que se colocaban en la parte superior de las casas para coronarlas. Siendo las femias redondeadas los machos son pinchos que apuntan al cielo. El simple ejercicio de voltearlos anula su agresividad puntiaguda, convirtiéndolos en vaso, jarrón y recipiente. Ambas obras funcionan como líneas horizontales en el espacio que conviven con otras obras verticales. En Las partes en las que tengo que plegar un rascacielos, tejas de pizarra se utilizan para calcular con tizas la relación entre mi altura y la de los edificios más altos de Nueva York. En Apañadeiras apañandose unhas ás outras construyo torres a partir de estas mujeres que además de sostener sus cargas, se sostienen a sí mismas y se miran las unas a las otras. En las cuatro obras tituladas Las faldas, en realidad, pueden ser los tejados de algo se invierten las colocaciones espaciales de pompones, faldas, pies y calcetines. Las antenas cerámicas sirven para elevar las estructuras unos centímetros más, las construcciones son edificios y también figura humana. Las obras en papel distribuidas por la sala son ejercicios de transparencias, superposiciones, pliegues y bolsillos. Aquí reunimos lo que se muestra y lo que se esconde. Lo que se encuentra y se guarda. Son prenda y dibujo, cuerpo, papel y vestimenta.

Mar Ramón Soriano

Estructuras

Columns

Torres

Rasca

Triangles

Contar

Sumar

Doblar

Cielo

Floors

Pies

Arriba

Palos

Alfileres

Piernas

Paredes

Cimientos

Cuerpos

Sostenerse

Uptown

Downtown

Express

Local

Subir

Crecer

Cruzar el río de Brooklyn a Manhattan

Todos nos preguntamos, cómo se empieza un viaje, se aprende, se decide volver, y finalmente, se retorna. Con un océano de por medio, una masa de agua que conecta ambos países, el viaje de Ruth Matilda Anderson, fue en cierta parte un experimento, como el de Mar Ramón, en una ciudad nueva, donde se idearon los primeros pensamientos sobre esta obra.

Investigar en el archivo de Ruth Matilda Anderson en Nueva York teletransporta en cierto punto a nuestros orígenes, donde podemos encontrarnos con lo conocido en terrenos completamente desconocidos. Una paradoja que una artista descubre cruzando de Brooklyn a Manhattan, de una casa física temporal, a una casa reconocible, en fotografías, cartas, registros. Subirse a un metro en Nueva York uptown o downtown significa escoger un camino totalmente distinto, sin embargo se utiliza la misma línea de transporte. Un viaje que va en ambas direcciones, se puede repetir. Mar juega con las transparencias como un engaño en los archivos, los bolsillos que esconden información secreta, los recovecos y esquinas para guardar tesoros.

La sorpresa ante códigos y mecanismos que se conocen en una ciudad inmensa hoy en día se pueden trasladar, a una mirada que va y vuelve, se pliega y repliega, comenzando a principios de siglo de una americana en Galicia.

Influenciada por uno de los oficios más antiguos del mundo, la alfarería, la obra se compone de piezas que poseen una combinación complementaria entre apoyo y ausencia, una similitud como la que los cacharreiros de Niñodaguia precisan con la ayuda de las equilibristas apañadeiras. Para elaborar objetos de alfarería y avanzar culturalmente como sociedad, el equilibrio de estas mujeres era imprescindible. Y es en el lenguaje de la artista, donde la silueta de apañadeiras trabajando se puede parecer a la de una animadora en faena. La figura norteamericana de cheerleader dice literalmente que lidera el ánimo. Al equipo, al logro, al triunfo. Y celebran la victoria.

Durante su producción hasta la fecha, Mar ha trabajado con barro, telas, algodones, pañuelos de papel, sacos y metáforas. Tensiones de objetos de pared, que también representan tensiones humanas, entre lo opulento y lo sencillo, y las diversas utilidades de un objeto, como las tejas que conforman un tejado, los cimientos de una casa, el valor de la entrada en un papel a un espacio o el número de un billete. Mirar hacia arriba, luego mirar hacia abajo y volver a mirar hacia arriba otra vez hace pensar en una pieza de cerámica popular, mezclada con el símbolo de un pompón, la estatura humana y su correspondencia a un rascacielos.

Elena Pérez-Ardá López

Febrero 2024, Brooklyn, Nueva York.

Placing damp bowls on the drying.

Se echa el baño. Putting on the enamel, on the inside only.

Se cuecen. Marchan en las cestas.

R. Matilda.

A veces es interesante mirarse desde la perspectiva del que te ha mirado antes. Otras veces lo es el mirar algo que nunca has visto pero que resulta de algún modo familiar. Existe una mirada que exotiza lo externo y también una que convierte en signo lo propio mediante su auto-representación repetida. Las dinámicas de poder se entrelazan entre el observador y el observado, también entre territorios y, de igual modo, pueden ejercerse de forma espacial a partir de los sistemas de colocación.

Esta muestra se asienta en dos viajes que son, en realidad, el mismo. El mío, de Galicia a Nueva York y de regreso a Galicia y el de Ruth Matilda Anderson, igual pero en sentido contrario. La relación entre ellos me permite trabajar con imágenes y significaciones de ambos territorios que se emplean y se analizan a través de diferentes capas de observación e interpretación.

En las imágenes capturadas por esta americana en Galicia en la década de los años veinte del siglo pasado, observamos prendas y camisas, tanto vestidas como colgadas para secarse. También contemplamos joyas y ornamentos, elementos utilizados para la fotografía, y trajes que no se visten, sino que son extraídos de armarios y arcones para su inmortalización. Este trabajo, necesario a nivel patrimonial, puede resultar engañoso si consideramos la imagen fotográfica como prueba de veracidad. De manera similar, observo la nueva ciudad desde mi perspectiva escudriñadora pero también turística del que mira y se sorprende en lo ya conocido. Lo familiar al haber visto este lugar en numerosas películas y también al visitar este archivo fotográfico de nuestro pasado.

Por otro lado, el extrañamiento de Galicia que emana de estas imágenes se produce también desde la mirada del que vive en ella, al observar un pasado diferente y unas ciudades transformadas. Mi extrañamiento se desplaza igualmente hacia lo nuevo: el tamaño de los edificios, los autobuses escolares o las animadoras americanas, que acaban interesándome tanto a nivel de estructura como por ser una actividad popularmente femenina y, además, algo denostada. Estas expertas en construcciones espaciales y sororidades tridimensionales me recuerdan a las apañadeiras de Niñodaguia, soportando enormes cestas de cacharros sobre sus cabezas. Los ejercicios y formaciones de animadoras y los sistemas de apilado y carga siguen unas normas físicas básicas de disposición y carga que pueden trasladarse al lenguaje escultórico. La verticalidad se presenta como una constante en esta significación de poderes, desde los rascacielos hasta el ímpetu humano por elevarse para obtener una posición privilegiada, para observar desde arriba y estar más cerca del cielo.

En Mirar hacia arriba, luego mirar hacia abajo y volver a mirar hacia arriba otra vez trabajo con lo que está encima de nosotros y lo que está debajo, lo poderoso y lo humilde. Pies y calcetines, cuerpos y ornamentos, tejados, cargas, antenas y pompones. Sus faldas plisadas y nuestras camisas se confunden con tejados y bolsillos. Los picos de aquí y de allí se mezclan con pies descalzos y también con calcetines, representación de aquello que está más cerca del suelo. Lo de arriba y lo de abajo significan y en las obras presentadas se transmutan. Lo puntiagudo ahora es vaso, recipiente o cuenco y lo que está más abajo, cerca de la tierra que sirve como cimiento del cuerpo se eleva. Las tejas funcionan como cuencos, las faldas no cubren nada. La bisutería funciona como ornamentación de bajo presupuesto, como pose y como representación. Esto alude de alguna forma al posado fotográfico, ponerse de domingo, los zapatos del domingo. Hay capas y capas y filtros y filtros transparentes proyectados sobre las imágenes por parte de la fotógrafa y también por parte de las receptoras de dicha fotografía. Esta superposición de transparencias me interesa como veladura y filtro.

Las formas propias de Niñodaguia se revisan y se transforman, en Oito femias deitadas y Oito machos recipientes, parto de formas de la alfarería tradicional de este contexto, volúmenes que se colocaban en la parte superior de las casas para coronarlas. Siendo las femias redondeadas los machos son pinchos que apuntan al cielo. El simple ejercicio de voltearlos anula su agresividad puntiaguda, convirtiéndolos en vaso, jarrón y recipiente. Ambas obras funcionan como líneas horizontales en el espacio que conviven con otras obras verticales. En Las partes en las que tengo que plegar un rascacielos, tejas de pizarra se utilizan para calcular con tizas la relación entre mi altura y la de los edificios más altos de Nueva York. En Apañadeiras apañandose unhas ás outras construyo torres a partir de estas mujeres que además de sostener sus cargas, se sostienen a sí mismas y se miran las unas a las otras. En las cuatro obras tituladas Las faldas, en realidad, pueden ser los tejados de algo se invierten las colocaciones espaciales de pompones, faldas, pies y calcetines. Las antenas cerámicas sirven para elevar las estructuras unos centímetros más, las construcciones son edificios y también figura humana. Las obras en papel distribuidas por la sala son ejercicios de transparencias, superposiciones, pliegues y bolsillos. Aquí reunimos lo que se muestra y lo que se esconde. Lo que se encuentra y se guarda. Son prenda y dibujo, cuerpo, papel y vestimenta.

Mar Ramón Soriano

Estructuras

Columns

Torres

Rasca

Triangles

Contar

Sumar

Doblar

Cielo

Floors

Pies

Arriba

Palos

Alfileres

Piernas

Paredes

Cimientos

Cuerpos

Sostenerse

Uptown

Downtown

Express

Local

Subir

Crecer

Cruzar el río de Brooklyn a Manhattan

Investigar en el archivo de Ruth Matilda Anderson en Nueva York teletransporta en cierto punto a nuestros orígenes, donde podemos encontrarnos con lo conocido en terrenos completamente desconocidos. Una paradoja que una artista descubre cruzando de Brooklyn a Manhattan, de una casa física temporal, a una casa reconocible, en fotografías, cartas, registros. Subirse a un metro en Nueva York uptown o downtown significa escoger un camino totalmente distinto, sin embargo se utiliza la misma línea de transporte. Un viaje que va en ambas direcciones, se puede repetir. Mar juega con las transparencias como un engaño en los archivos, los bolsillos que esconden información secreta, los recovecos y esquinas para guardar tesoros.

La sorpresa ante códigos y mecanismos que se conocen en una ciudad inmensa hoy en día se pueden trasladar, a una mirada que va y vuelve, se pliega y repliega, comenzando a principios de siglo de una americana en Galicia.

Influenciada por uno de los oficios más antiguos del mundo, la alfarería, la obra se compone de piezas que poseen una combinación complementaria entre apoyo y ausencia, una similitud como la que los cacharreiros de Niñodaguia precisan con la ayuda de las equilibristas apañadeiras. Para elaborar objetos de alfarería y avanzar culturalmente como sociedad, el equilibrio de estas mujeres era imprescindible. Y es en el lenguaje de la artista, donde la silueta de apañadeiras trabajando se puede parecer a la de una animadora en faena. La figura norteamericana de cheerleader dice literalmente que lidera el ánimo. Al equipo, al logro, al triunfo. Y celebran la victoria.

Durante su producción hasta la fecha, Mar ha trabajado con barro, telas, algodones, pañuelos de papel, sacos y metáforas. Tensiones de objetos de pared, que también representan tensiones humanas, entre lo opulento y lo sencillo, y las diversas utilidades de un objeto, como las tejas que conforman un tejado, los cimientos de una casa, el valor de la entrada en un papel a un espacio o el número de un billete. Mirar hacia arriba, luego mirar hacia abajo y volver a mirar hacia arriba otra vez hace pensar en una pieza de cerámica popular, mezclada con el símbolo de un pompón, la estatura humana y su correspondencia a un rascacielos.

Elena Pérez-Ardá López

Febrero 2024, Brooklyn, Nueva York.

Dry in the sun, if any.

Placing damp bowls on the drying.

Putting on the enamel. Putting on the enamel, on the inside only.

They are cooked. They march in the baskets.

R. Matilda.

Sometimes it is interesting to look at yourself from the perspective of one who has looked at you before. At other times it is interesting to look at something you have never seen but which is somehow familiar. There is a gaze that exoticizes the external and also one that turns one's own into a sign through its repeated self-representation. The dynamics of power are intertwined between the observer and the observed, also between territories and, in the same way, they can be exercised spatially from the systems of placement.

This exhibition is based on two journeys that are, in reality, the same. Mine, from Galicia to New York and back to Galicia, and Ruth Matilda Anderson's, the same but in the opposite direction. The relationship between them allows me to work with images and meanings of both territories that are used and analyzed through different layers of observation and interpretation.

In the images captured by this American in Galicia in the twenties of the last century, we observe garments and shirts, both dressed and hung to dry. We also contemplate jewelry and ornaments, elements used for photography, and costumes that are not dressed, but extracted from closets and chests for their immortalization. This work, necessary at the patrimonial level, can be misleading if we consider the photographic image as proof of veracity. Similarly, I observe the new city from my scrutinizing but also touristic perspective of the one who looks and is surprised by what is already known. The familiar having seen this place in numerous films and also by visiting this photographic archive of our past.

On the other hand, the estrangement of Galicia that emanates from these images is also produced from the gaze of the person who lives there, observing a different past and transformed cities. My estrangement also moves towards the new: the size of the buildings, the school buses or the American cheerleaders, which end up interesting me both in terms of structure and for being a popularly feminine activity and, moreover, somewhat reviled. These experts in spatial constructions and three-dimensional sororities remind me of Niñodaguia's apañadeiras, carrying huge baskets of pots and pans on their heads. The exercises and formations of cheerleaders and the stacking and loading systems follow basic physical rules of arrangement and loading that can be transferred to the sculptural language. Verticality is presented as a constant in this signification of powers, from skyscrapers to the human impetus to rise to obtain a privileged position, to observe from above and be closer to the sky.

In Looking up, then looking down and looking up again I work with what is above us and what is below us, the powerful and the humble. Feet and socks, bodies and ornaments, roofs, loads, antennae and pom-poms. Their pleated skirts and our shirts are confused with roofs and pockets. The peaks here and there are mixed with bare feet and also with socks, representing that which is closer to the ground. What is above and what is below signify and in the works presented are transmuted. What is pointed is now a glass, container or bowl and what is lower, near the earth that serves as the foundation of the body, is elevated. The tiles function as bowls, the skirts cover nothing. The costume jewelry functions as low-budget ornamentation, as pose and as representation. This alludes somehow to photographic posing, putting on Sunday, Sunday shoes. There are layers and layers and layers and filters and transparent filters projected on the images by the photographer and also by the recipients of the photograph. This superimposition of transparencies interests me as a glaze and filter.

Niñodaguia's own forms are revised and transformed, in Oito femias deitadas and Oito machos recipientes, based on traditional pottery forms of this context, volumes that were placed on top of the houses to crown them. Being the femias rounded, the males are spikes pointing to the sky. The simple exercise of turning them upside down annuls their sharp aggressiveness, turning them into a vase, a vase and a vessel. Both works function as horizontal lines in space that coexist with other vertical works. In The parts where I have to fold a skyscraper, slate tiles are used to calculate with chalk the relationship between my height and that of the tallest buildings in New York. In Apañadeiras apañandose unhas ás outras I build towers out of these women who, in addition to holding their loads, hold themselves up and look at each other. In the four works titled The skirts, in reality, can be the roofs of something, the spatial placements of pompoms, skirts, feet and socks are inverted. The ceramic antennas serve to raise the structures a few centimeters higher, the constructions are buildings and also human figures. The works on paper distributed around the room are exercises in transparencies, superimpositions, folds and pockets. Here we bring together what is shown and what is hidden. What is found and what is kept. They are both garment and garment.

We all wonder how to start a journey, learn, decide to return, and finally return. With an ocean in between, a body of water that connects both countries, Ruth Matilda Anderson's journey was to some extent an experiment, like Mar Ramón's, in a new city, where the first thoughts about this work were conceived.

Researching in Ruth Matilda Anderson's archive in New York teleports at a certain point to our origins, where we can encounter the known in completely unknown terrain. A paradox that an artist discovers crossing from Brooklyn to Manhattan, from a temporary physical home, to a recognizable home, in photographs, letters, records. Getting on a subway in New York uptown or downtown means choosing a totally different path, yet using the same line of transportation. A journey that goes in both directions can be repeated. Mar plays with transparencies as a deception in the archives, the pockets that hide secret information, the nooks and corners to keep treasures.

The surprise before codes and mechanisms that are known in a huge city today can be transferred, to a look that goes back and forth, folds and folds back, starting at the beginning of the century of an American in Galicia.

Influenced by one of the oldest crafts in the world, pottery, the work is composed of pieces that have a complementary combination of support and absence, a similarity like the one that the cacharreiros of Niñodaguia require with the help of the apañadeira balancers. In order to elaborate pottery objects and advance culturally as a society, the balance of these women was essential. And it is in the artist's language, where the silhouette of apañadeiras at work can resemble that of a cheerleader at work. The North American figure of cheerleader literally says that she leads the cheer. To the team, to the achievement, to the triumph. And they celebrate victory.

During her production to date, Mar has worked with clay, fabrics, cottons, tissues, sacks and metaphors. Tensions of wall objects, which also represent human tensions, between the opulent and the simple, and the various utilities of an object, such as the tiles that make up a roof, the foundations of a house, the value of the entrance on a piece of paper to a space or the number on a bill. Looking up, then looking down and looking up again makes one think of a piece of popular pottery, mixed with the symbol of a pompom, the human stature and its correspondence to a skyscraper.

Placing damp bowls on the drying.

Putting on the enamel. Putting on the enamel, on the inside only.

They are cooked. They march in the baskets.

R. Matilda.

Sometimes it is interesting to look at yourself from the perspective of one who has looked at you before. At other times it is interesting to look at something you have never seen but which is somehow familiar. There is a gaze that exoticizes the external and also one that turns one's own into a sign through its repeated self-representation. The dynamics of power are intertwined between the observer and the observed, also between territories and, in the same way, they can be exercised spatially from the systems of placement.

This exhibition is based on two journeys that are, in reality, the same. Mine, from Galicia to New York and back to Galicia, and Ruth Matilda Anderson's, the same but in the opposite direction. The relationship between them allows me to work with images and meanings of both territories that are used and analyzed through different layers of observation and interpretation.

In the images captured by this American in Galicia in the twenties of the last century, we observe garments and shirts, both dressed and hung to dry. We also contemplate jewelry and ornaments, elements used for photography, and costumes that are not dressed, but extracted from closets and chests for their immortalization. This work, necessary at the patrimonial level, can be misleading if we consider the photographic image as proof of veracity. Similarly, I observe the new city from my scrutinizing but also touristic perspective of the one who looks and is surprised by what is already known. The familiar having seen this place in numerous films and also by visiting this photographic archive of our past.

On the other hand, the estrangement of Galicia that emanates from these images is also produced from the gaze of the person who lives there, observing a different past and transformed cities. My estrangement also moves towards the new: the size of the buildings, the school buses or the American cheerleaders, which end up interesting me both in terms of structure and for being a popularly feminine activity and, moreover, somewhat reviled. These experts in spatial constructions and three-dimensional sororities remind me of Niñodaguia's apañadeiras, carrying huge baskets of pots and pans on their heads. The exercises and formations of cheerleaders and the stacking and loading systems follow basic physical rules of arrangement and loading that can be transferred to the sculptural language. Verticality is presented as a constant in this signification of powers, from skyscrapers to the human impetus to rise to obtain a privileged position, to observe from above and be closer to the sky.

In Looking up, then looking down and looking up again I work with what is above us and what is below us, the powerful and the humble. Feet and socks, bodies and ornaments, roofs, loads, antennae and pom-poms. Their pleated skirts and our shirts are confused with roofs and pockets. The peaks here and there are mixed with bare feet and also with socks, representing that which is closer to the ground. What is above and what is below signify and in the works presented are transmuted. What is pointed is now a glass, container or bowl and what is lower, near the earth that serves as the foundation of the body, is elevated. The tiles function as bowls, the skirts cover nothing. The costume jewelry functions as low-budget ornamentation, as pose and as representation. This alludes somehow to photographic posing, putting on Sunday, Sunday shoes. There are layers and layers and layers and filters and transparent filters projected on the images by the photographer and also by the recipients of the photograph. This superimposition of transparencies interests me as a glaze and filter.

Niñodaguia's own forms are revised and transformed, in Oito femias deitadas and Oito machos recipientes, based on traditional pottery forms of this context, volumes that were placed on top of the houses to crown them. Being the femias rounded, the males are spikes pointing to the sky. The simple exercise of turning them upside down annuls their sharp aggressiveness, turning them into a vase, a vase and a vessel. Both works function as horizontal lines in space that coexist with other vertical works. In The parts where I have to fold a skyscraper, slate tiles are used to calculate with chalk the relationship between my height and that of the tallest buildings in New York. In Apañadeiras apañandose unhas ás outras I build towers out of these women who, in addition to holding their loads, hold themselves up and look at each other. In the four works titled The skirts, in reality, can be the roofs of something, the spatial placements of pompoms, skirts, feet and socks are inverted. The ceramic antennas serve to raise the structures a few centimeters higher, the constructions are buildings and also human figures. The works on paper distributed around the room are exercises in transparencies, superimpositions, folds and pockets. Here we bring together what is shown and what is hidden. What is found and what is kept. They are both garment and garment.

Structures

Columns

Towers

Scraper

Triangles

Count

Add

Fold

Sky

Floors

Feet

Top

Sticks

Pins

Legs

Walls

Foundations

Bodies

Support

Uptown

Downtown

Express

Local

Upload

Grow up

Columns

Towers

Scraper

Triangles

Count

Add

Fold

Sky

Floors

Feet

Top

Sticks

Pins

Legs

Walls

Foundations

Bodies

Support

Uptown

Downtown

Express

Local

Upload

Grow up

Crossing the river from Brooklyn to Manhattan

We all wonder how to start a journey, learn, decide to return, and finally return. With an ocean in between, a body of water that connects both countries, Ruth Matilda Anderson's journey was to some extent an experiment, like Mar Ramón's, in a new city, where the first thoughts about this work were conceived.

Researching in Ruth Matilda Anderson's archive in New York teleports at a certain point to our origins, where we can encounter the known in completely unknown terrain. A paradox that an artist discovers crossing from Brooklyn to Manhattan, from a temporary physical home, to a recognizable home, in photographs, letters, records. Getting on a subway in New York uptown or downtown means choosing a totally different path, yet using the same line of transportation. A journey that goes in both directions can be repeated. Mar plays with transparencies as a deception in the archives, the pockets that hide secret information, the nooks and corners to keep treasures.

The surprise before codes and mechanisms that are known in a huge city today can be transferred, to a look that goes back and forth, folds and folds back, starting at the beginning of the century of an American in Galicia.

Influenced by one of the oldest crafts in the world, pottery, the work is composed of pieces that have a complementary combination of support and absence, a similarity like the one that the cacharreiros of Niñodaguia require with the help of the apañadeira balancers. In order to elaborate pottery objects and advance culturally as a society, the balance of these women was essential. And it is in the artist's language, where the silhouette of apañadeiras at work can resemble that of a cheerleader at work. The North American figure of cheerleader literally says that she leads the cheer. To the team, to the achievement, to the triumph. And they celebrate victory.

During her production to date, Mar has worked with clay, fabrics, cottons, tissues, sacks and metaphors. Tensions of wall objects, which also represent human tensions, between the opulent and the simple, and the various utilities of an object, such as the tiles that make up a roof, the foundations of a house, the value of the entrance on a piece of paper to a space or the number on a bill. Looking up, then looking down and looking up again makes one think of a piece of popular pottery, mixed with the symbol of a pompom, the human stature and its correspondence to a skyscraper.